Mon, 17 Oct 2022

Born Old

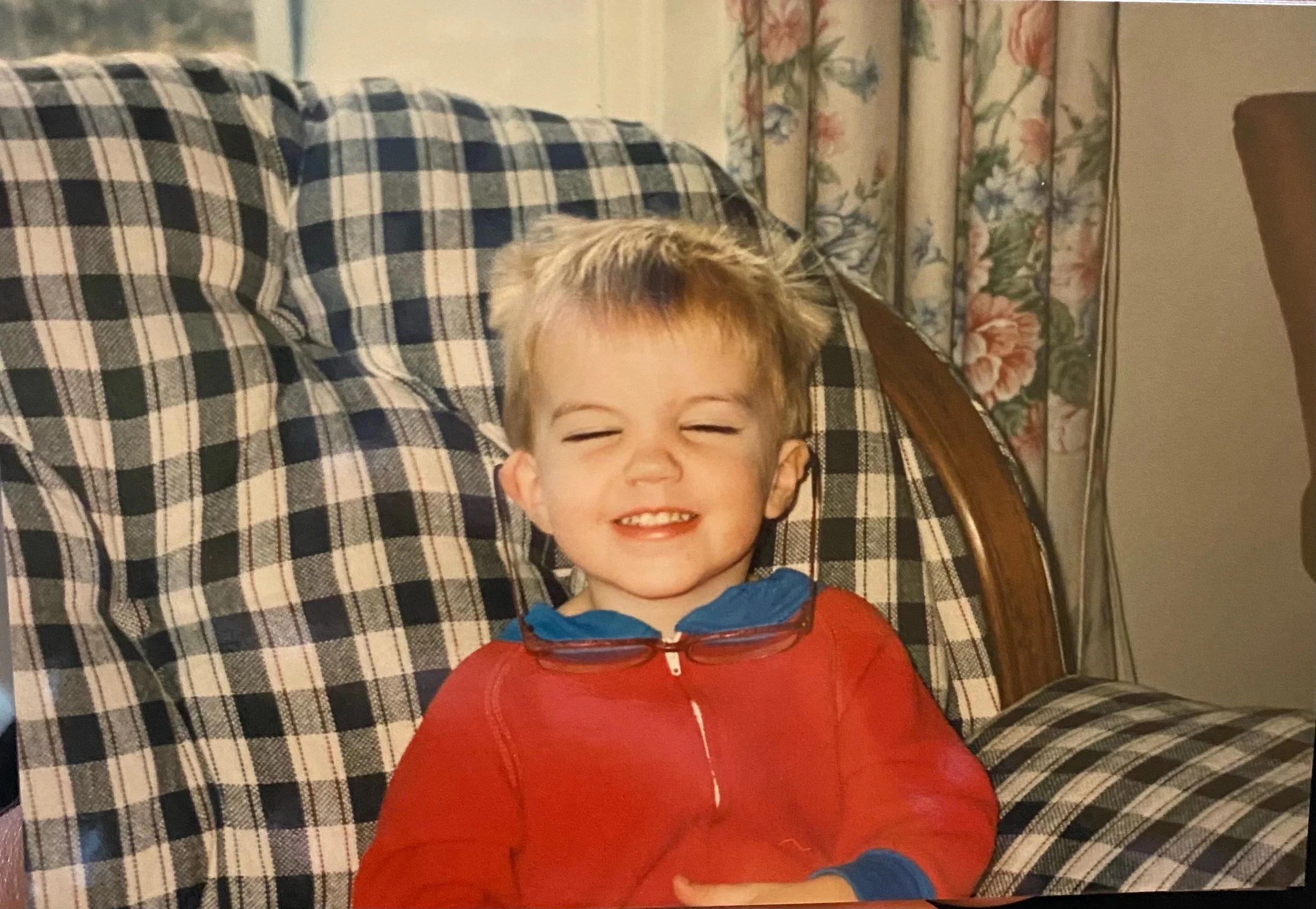

I've often joked, "I was born old." I’ve always been "an old soul." I was "mature for my age." I recall, on a number of occasions in my early twenties, when folks would learn my age, their incredulity was palpable. "You're twenty-two? You don't seem twenty-two. You're not like most twenty-two year olds I know." And to be fair, they weren't wrong; I wasn't like most twenty-two year olds.

The truth is, I wasn't born old. I was born the normal age. I simply aged quickly. I continue to age quickly. Recent self-revelation has led me to a few reluctant conclusions: a) if I am to grow chronologically old, I must slow my cognitive and emotional aging, b) based on current observations and recollections from childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood, I have an acute ability to determine when my base assumptions and predispositions are "wrong", irrespective of whether I understand why, and adjust my behavior accordingly to an impressive—albeit problematic—degree, and c) because of this, my cognitive/emotional aging quickens by the day and, eventually, the body will catch up with the mind.

I've known for a long time that I will never actually grow old.

***

In a way I’ve struggled to adequately describe, I had this sense from an early age that I was fundamentally wrong. A number of factors provided cover for what was really going on. And I say this with a considerable grain of salt: “what was really going on.” That’s an ever-changing picture as I continue to learn new information, which, I suppose, is how it should be. But fuck me if the picture doesn’t just keep getting darker.

Raised in a high-control religious culture, I bought in hard. The first philosophical conclusion I remember making for myself was that of Original Sin at around the age of four or five. The belief that sin was original to who I was—to my very essence—was not challenging math, even for such a small child: if humankind is evil, and if I am human, then I am evil. This was the first concept I explicitly, consciously internalized. It became foundational to my entire identity. Not a great starting point.

I have always been extremely receptive to positive and negative reinforcement. I learned quickly how to be and how not to be—whether through direct punishment or reward, or by observing the same in others, or by hearing about the same in theoretical others. I was hypervigilant, policing my every thought and action, obsessing over being better, fearful of Hell and ostracism. When I saw—or heard about—someone else doing something that earned them a punishment, no matter how trivial or severe the behavior or punishment was, I noted it and vowed to make every effort to never do the same so as to avoid a similar fate.

If I was rewarded for doing something good or doing something right (as determined by whatever arbitrary rules I lived under while religious), I would internalize that as well and seek out opportunities for a repeat performance, even though I often didn’t understand why it was good or right.

And here we see the formation of my first mask, which eventually bifurcated and then multiplied into myriad forms, dependent upon setting and group.

Because of these masks, I was well liked by both authority figures and peers. I knew how to get in people’s good graces. I’ve always had this uncanny (and oftentimes unsettling) understanding that—almost regardless of the individual or group—people think I am unequivocally on their side.

The first time I noticed this was in high school when two people I knew were fighting. Each of them separately confided in me in such a way that I could tell they both believed I was entirely in alignment with their respective and mutually exclusive points of view. In truth, I was on neither side and did my best to remain noncommittal, but I never disavowed either of their beliefs in my unwavering allyship.

***

Depression enveloped me in adolescence, which was the result of attempting to hide, to pass as whatever it was I believed everyone else wanted. The energy expenditure of existing like this is immense, but because the effects didn’t present themselves until these masks were so deeply ingrained in the way I moved through the world, I was unable to establish a clear delineation between cause and effect.

Instead, the depression just became more evidence that I was fundamentally wrong and broken and in need of saving. I couldn’t let anyone know just how completely fucked in the head I was because then I would surely be cast out and ostracized—rejected by everyone, be they human or god.

So I doubled down. I became all things to all people. I ignored my own sense of self. Who I was didn’t matter; it was wrong anyway. Why would I want to be myself when I am the embodiment of sin and unholiness? No, I had to be anything but myself.

After grad school, I joined the workforce. I had a tough time finding a job and jumped at the first real opportunity I got, which was in customer service. I could not possibly have known at the time, but working in customer service dropped the gas pedal to the floor in my race to dissociate from anything innate to myself. Again, though, this acceleration was hidden, largely because the industry I joined was the running industry.

Running is the only time I truly experience myself in no uncertain terms. I don’t mask when I run; I don’t know if I can mask while running. It is the only form of true, unadulterated self-expression for me.

But while I was at work, I was everything but myself. And my “customer service voice” began to creep, bleed into every other facet of my life: my personal relationships, attempted romantic relationships, even passersby on the street. I was hemorrhaging cognitive and emotional energy and I had no idea.

Predictably, depression accelerated in tandem.

***

When I finally identified my Autism, everything suddenly made sense. The flood of relief was incredible. I’ve never experienced anything like it. But, like any box Pandora gives you, this, too, had consequences I couldn’t possibly have been prepared for.

Ironically or fittingly (you be the judge), the very same podcast that prompted my search for an Autism diagnosis also recently gave voice to the way I’ve been experiencing life post-diagnosis: it feels like I’m becoming “more Autistic.”

I’m not actually becoming more Autistic. I’m already all the way Autistic. Full-time Autist over here. But, apparently, this phenomenon is a common one for late-diagnosed Autistics. Immediately after identifying one’s Autism, there’s relief, and then the overwhelming realization and understanding that the masks we’ve been donning are killing us. And you’d think it would be helpful to identify the mechanism of your demise, especially when it is behavioral and thus, in theory, malleable, adjustable.

But it’s all too much. I don’t know who I am without my masks. Set aside the fact that I literally don’t know how to unmask yet, even if I could, who would I be? All I’ve ever known is how to not be myself. I don’t get to flip a switch and decide to just be myself now, especially not unapologetically.

I am an active partner in my own premature death and I’ve only just now fully grasped this. And it’s not like I want to die young. I know this. I’m just so, so fucking tired. Maybe this is just the price you pay for being “mature for your age.”

***

It goes like this.

A creature from elsewhere is placed with a pair of human parents. This creature is not told where he’s from (nor are his parents). He’s given the same training as his human peers, and even shares their physical form. But when he was put here—on this planet earth, with his human parents—his kind (those who left him here) neglected to remove the innate qualities within him that harken back to his true nature. In fact, they come so seamlessly and so naturally to him that he thinks nothing of them at all until they’re juxtaposed in stark terms against the prevailing human culture.

By seeing how others behave, he learns quickly that what comes naturally to him is incorrect. He pathologizes his instincts. He’s easily confused by the words, actions, and intentions of others but he doesn’t know why. So he pretends: pretends he understands, pretends to be human.

He sees others say things they don’t mean. It never, ever, ever ceases to perplex him. He slowly realizes that—for some reason—humans often say one thing and then do something else entirely. He even joins in this confusing charade at times.

But often he forgets to play this befuddling game. He forgets that others can be insincere. He forgets that others have ulterior motives. He gets taken advantage of. He gets taken for granted. He holds up his end of the bargain and waits, and waits, and waits, and finally he realizes that the bargain was his alone. Whether or not they intended to hurt him is irrelevant. He is hurt. Over and over again.

He is always lonely.

And then, by some cosmic act of either cruelty or kindness, he learns that, in fact, he is not like the humans around him. He is something else, something that makes much, much more intrinsic sense to him. At first this is reassuring. It’s validating.

He finally understands why so many things are so much harder for him than his human compatriots. He realizes he’s not broken; he is actually quite whole. And he loves himself, perhaps for the first time, and he also realizes that he is one among many, not one alone.

But almost as soon as he believes things will get better from here, something else happens. He recognizes just how virulently antithetical to his basic needs is the world in which he lives. He doesn’t actually know how to relax and be himself in a world that punishes people like him for being who they are. Things that have always bothered him become suddenly unbearable. Anxieties he’s always had and always borne are now insufferable and gargantuan. Little sensory issues he used to ignore—or simply power through—become overwhelming to the point of physiological distress, creating the need for a somatic outlet of intensity great enough to break his bones.

He seeks others out, those of his own kind: those who have experienced that which he’s experiencing, those who know exactly what he means without him needing to explain, those who say exactly what they mean without him needing to guess. And he listens to their stories.

Far too many have already killed themselves, he learns. Far too many still will. He fears he may be one of them, just another tragic datum informing a deeply troubling statistic. But there are some—ambiguously innumerable—who survived. Some have found a way through; they found a better existence, a sustainable, even enjoyable, state of being.

He struggles to see that for himself. When he looks too far into the future, he sees only darkness, only suffering, only loneliness and isolation, unceasing and without end.

So he doesn’t look to the future. He looks to his next singular step forward. And the next one. And the one after that. Only ever the next step. It’s all he can do. And he hopes it’s enough. He’s been told it is.

But then, he’s been told things before.

Even so, what has he left to lose? The next step it is.